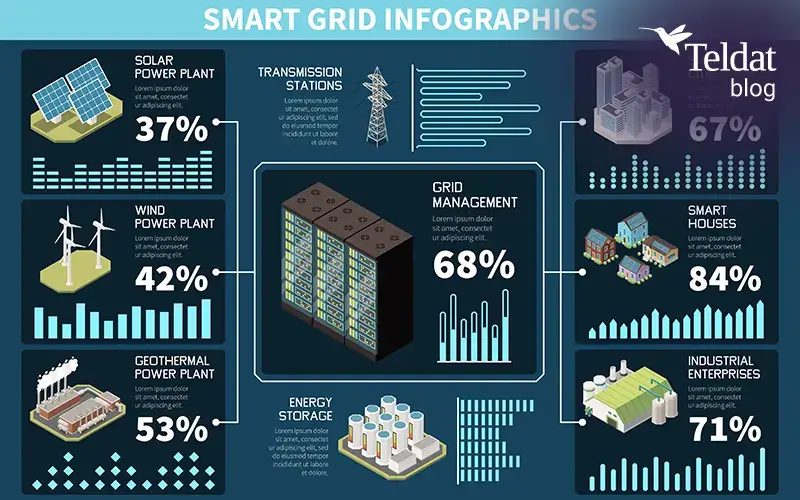

The digital transformation of the electricity sector has accelerated the adoption of Smart Grids: advanced energy infrastructures that integrate distributed generation, active demand response systems, and real-time bidirectional communication mechanisms enabled by digital technologies. This paradigm shift represents far more than a simple technological upgrade; it marks a fundamental change in how electricity is produced, distributed, and consumed.

However, this evolution also brings significant challenges. The convergence of Operational Technology (OT) and Information Technology (IT) environments—combined with increasingly complex network topologies made up of thousands of unattended remote points and interconnected field devices—has dramatically expanded the attack surface. New vulnerabilities and intrusion vectors are emerging as a result. In this context, Smart Grid cybersecurity has become a strategic pillar for ensuring the availability, integrity, and resilience of critical energy infrastructures against targeted attacks and persistent threats.

This blog post explores the current cybersecurity threat landscape affecting Smart Grids, examines the protection strategies available today, and reflects on the essential role cybersecurity must play in the design and operation of these critical infrastructures.

New threats in Cybersecurity for Smart Grids

Due to their hybrid and distributed nature, Smart Grids present a risk profile that is significantly more complex than that of traditional power grids. The rapid proliferation of connected devices—from smart meters to substation automation systems—exponentially increases the number of potential entry points for malicious actors. Unlike the centralized systems of the past, where perimeter security could provide a certain level of protection, modern Smart Grid networks require a fundamentally different security approach.

Cyberattacks targeting Smart Grids can have devastating consequences: prolonged power outages affecting millions of users, manipulation of measurement data that distorts energy markets, unauthorized access to control systems enabling changes to critical operating parameters, and even permanent physical damage to high-value equipment caused by altered operating conditions.

Among the most significant and sophisticated threats is malware specifically designed to target SCADA (Supervisory Control and Data Acquisition) systems, as demonstrated by high-profile incidents that have impacted energy infrastructures in multiple countries. Distributed denial-of-service (DDoS) attacks represent another serious threat, capable of saturating critical communications between control centers and distributed assets. In addition, intrusions into communication links—particularly wireless or long-distance connections—can allow attackers to intercept sensitive information or inject fraudulent commands.

Of particular concern is the exploitation of vulnerabilities in field devices, many of which were designed long before cybersecurity was considered a fundamental requirement. These legacy devices, now connected to IP networks, introduce attack vectors ranging from unchanged default credentials to unencrypted communication protocols that transmit information in plain text.

Protection strategies

Effective protection of Smart Grids requires a multi-layered approach that encompasses technological, organizational, and human dimensions. There is no single or “magic” solution: security must be built through the intelligent combination of multiple complementary controls operating at different levels of the architecture.

Network segmentation is a fundamental pillar of this defensive strategy. By defining differentiated security zones and implementing strict controls at the connection points between them, critical areas can be isolated and the lateral spread of threats significantly reduced. This segmentation must be designed with more than just the physical network topology in mind; data flows and the specific operational requirements of each zone must also be taken into account.

The use of secure protocols for data transport represents another essential layer of protection. Technologies such as TLS (Transport Layer Security) for application-level communications, IPsec for network-level protection, and MACsec for link-layer security must be deployed in a coordinated manner, tailored to the specific characteristics of each communication segment. The selection of the most appropriate protocol depends on factors such as available bandwidth, acceptable latency, and the processing capabilities of endpoint devices.

Robust authentication mechanisms and effective identity management ensure that only authorized users and devices can access critical resources. This requires moving beyond traditional username-and-password combinations to incorporate multi-factor authentication, digital certificates for devices, and centralized identity management systems capable of enabling rapid detection and response to security incidents.

Continuous monitoring using intrusion detection and prevention systems (IDS/IPS) provides real-time visibility into what is happening across the network and enables the detection of anomalous behavior that may indicate an ongoing attack. These systems must be specifically configured for industrial environments, where traffic patterns and operational behavior differ significantly from those found in traditional corporate networks.

Regulatory frameworks and best practices

The development and adoption of cybersecurity regulations tailored to critical infrastructures have provided valuable reference frameworks for assessing risk and defining protection policies appropriate to each layer of the infrastructure.

The IEC 62443 standard has established itself as the international benchmark for the security of industrial control and automation systems. Its approach—based on security zones and conduits, together with its classification of security levels—offers a structured methodology for designing, implementing, and maintaining security in OT environments.

In North America, the NERC CIP (North American Electric Reliability Corporation Critical Infrastructure Protection) standards define specific requirements for power system operators, covering aspects that range from personnel management to the physical and cyber protection of critical assets.

Within the European context, the NIS2 (Network and Information Security) Directive represents a significant step forward in the regulation of cybersecurity for critical infrastructures. It expands the scope of regulated sectors and strengthens requirements for incident reporting and risk management. Crucially, the directive explicitly recognizes that cybersecurity is not merely a technical challenge, but a governance issue that requires the active involvement of senior management.

Conclusion: towards native cybersecurity

The analysis presented shows that Smart Grids represent a qualitative leap in energy management, while also introducing unprecedented security challenges. IT-OT convergence, the rapid proliferation of connected devices, and the critical nature of the services provided create an environment in which cybersecurity can no longer be treated as an additional or complementary feature.

Because Smart Grids are critical infrastructure on which entire societies depend, cybersecurity must cease to be an add-on and instead become a native function of Smart Grid design. This means that security considerations must be embedded from the earliest stages of system conception and design, rather than applied later as a corrective measure to address inherent vulnerabilities.

The adoption of standards such as IEC 62443, NERC CIP, and NIS2 provides valuable guidance, but effective implementation requires an organizational commitment that goes beyond formal compliance. Energy-sector organizations must foster a genuine cybersecurity culture that permeates every level of the organization, from senior management to field technicians.

The future of Smart Grids depends on our collective ability to build systems that are simultaneously efficient, sustainable, and secure. Cybersecurity is not the cost of digitization; it is the foundation that ensures not only a reliable electricity supply, but also trust in a distributed, automated energy system prepared to meet future challenges.

Only through a holistic approach that combines advanced technology, robust processes, appropriate regulatory frameworks, and continuous awareness can we fully harness the transformative potential of Smart Grids while mitigating the risks inherent in their hyperconnected nature. Security and innovation are not opposing goals, but complementary pillars in the construction of the electricity grid of the 21st century.

At Teldat, we have many years of experience working with data-related technologies in Smart Grid environments, both in communications and in cybersecurity, and we believe that this experience places us in a strong position within this market.